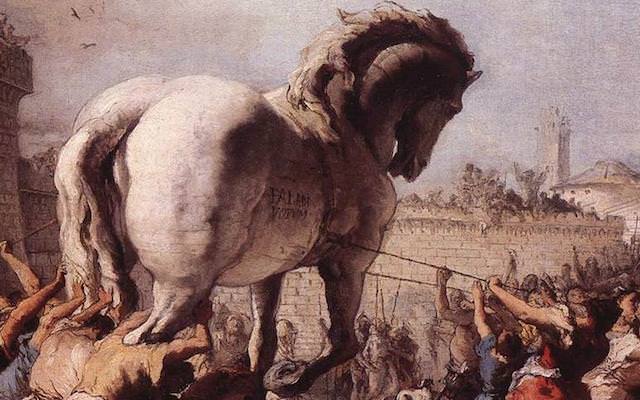

During the mythical Trojan War, the goddess Artemis punished Agamemnon, the Greek general, for evil deeds his soldiers committed. On their way to the war, Artemis caused the winds to stir and their ships were knocked violently into one another. Agamemnon learned that the only way to appease the wrath of Artemis was to sacrifice his daughter to her, so he sent for his daughter and sacrificed her to the goddess. With the anger of the goddess quenched, the ships reached Troy without any more difficulty. The Trojan War legend was written about 1000 years before Christ was born, and it shows that people throughout history, even those who believed in multiple gods, had a sense that their sins must be dealt with, that the wrath of the gods must be satisfied.

Unlike the gods depicted in Greek mythology, our God alone rules and reigns. There is no deficiency in His character, no need for another god. He is the Lord, and He will share His glory with no one. Because He is holy and righteous, His wrath burns against sin. His wrath must be quenched, must be satisfied.

The word used in the New Testament to capture God’s wrath being satisfied is “propitiation.” In Jesus’ story of the Pharisee and the tax collector, the tax collector uses the word, which is often translated “be merciful to me” or “turn your wrath from me” as he recognizes his sinfulness and pleads for mercy (Luke 18:13). The Pharisee thanks God that he is not like others, even the tax collector, and rejoices in his own goodness, the things he does for God. Jesus says that the tax collector, not the Pharisee, goes home justified.

The temple is the scene of Jesus’ parable. At the temple, on the annual Day of Atonement, the high priest would sacrifice a goat and take the blood into the Most Holy Place and sprinkle it on the seat of propitiation, the lid of the Ark of the Covenant. Inside the Ark were the Ten Commandments—the Law that reveals us to be sinful because we have never been able to live up it. We have sinned against His Law, violated His holiness, and we stand condemned before it. But the blood sprinkled on the seat of propitiation signified that God’s wrath was being appeased. Symbolically, His wrath was turned from His people and placed on the goat that was sacrificed. The sacrifice received the punishment instead of the people. Another goat would be brought to the priest. Instead of killing this goat, the priest would put his hands on the goat’s head to symbolize that the sins of the people were transferred to the goat. The goat was then led out of the city and set free in the wilderness as a symbol that the sin was separated from the people. Their sins could be forgiven as God’s holy wrath was satisfied.

The tax collector gets this. He is outside the temple and is essentially saying, “God let those sacrifices bear my sin. I know that because you are holy, you can’t just forget my sin. It has to be punished. Please, God, turn your wrath for my sin away from me.” Unlike Agamemnon, the Greek general, the tax collector does not seek to sacrifice something. Because he understands his own sinfulness, he does not look to himself to appease the wrath of God. He looks to God. In his classic work, Knowing God, J.I. Packer writes:

In paganism, man propitiates his gods and religion becomes a form of commercialism and, indeed, of bribery. In Christianity, however, God propitiates His wrath by His own actions . . . It was God Himself who took the initiative in quenching His own wrath.

Packer calls propitiation “the heart of the Christian gospel.” Our God does not ask us for a sacrifice to appease His holy wrath. Instead of demanding our child, like Artemis, He offers His Son. Jesus is our propitiation. He is the perfect once and for all sacrifice, and the fulfillment of all the sacrifices offered in the temple. On the cross, He absorbed the wrath of God in our place so that our sins may be removed from us. His sacrifice is all-sufficient.