An unprecedented 20 superhero movies are expected to come to movie theaters between 2018 and 2020. Superhero movies are on the rise and people rave about the heroes in Black Panther, Avengers, and Spider-Man. Where does our longing for superheroes come from?

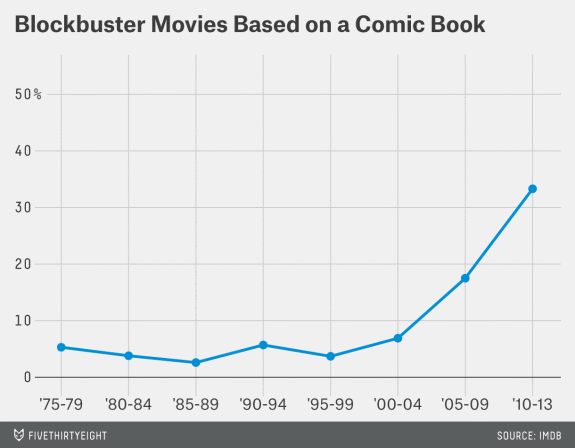

The ABC News story, “Superheroes, Why Are We Obsessed?” declared we need superheroes in our lives. David Wright of ABC News reported, “Things changed with the attacks of September 11, 2001. The world once again divided into good and evil but morally complicated and flawed and vulnerable. Suddenly superheroes came back in a big way.” Others have also made the connection between September 11th and our culture’s fascination with superheroes, noting that the villains are now much more complex representations of our inhumanity. The data confirms the observations of Wright and others. Notice the inflection point on the graph provided by FiveThirtyEight. Blockbuster releases based on comics rose sharply post-9/11.

When Spiderman was released in 2002, it broke a slew of blockbuster records as people flocked to the theaters to see a hero. Film observers have called it the watershed moment that ushered in the rapid expansion of comic superhero movies. There are at least three things the rise of comic superheroes tells us:

1. We know we are broken.

The first comic superheroes became popular nearly eighty years ago during the oppressive era of the Great Depression and the beginning of World War II. They reached a tipping point in popularity post-9/11 and further grew through the recession in 2008. We don’t look for a Savior unless we first realize we are broken and in need of rescue.

2. We want to be rescued.

Emptiness and pain alert us to our need to be saved. The flocking of people to superhero films reveals a longing to be saved from the brokenness of this life and this world.

3. And this is good.

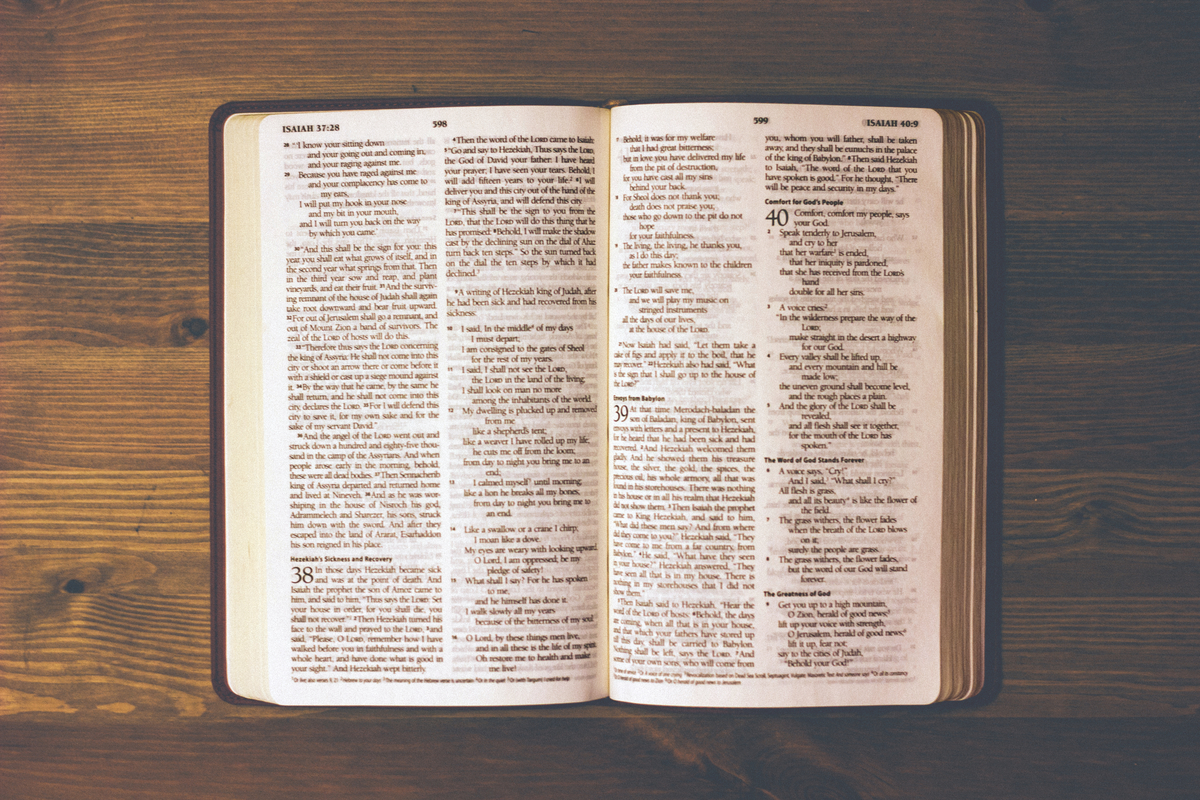

C.S. Lewis and J.R.R Tolkien would likely think our culture’s fascination with superhero myths is a good thing because it reveals our longing for the Gospel story. As authors and friends they shared a special kinship, and before Lewis placed his faith in Christ, he had an important conversation with Tolkien. Lewis struggled to see how the death of Christ hundreds of years before had any bearing on his life, but he was moved by myths and stories of the day. Tolkien told him “There are in myths, memories of the un-fallen world, a sense of the shame and tragedy of the brokenness of our present life; and there are hints of the promise and hope of redemption, The Gospel is the true myth, the great fairy story.” A few days later Lewis became a Christian.

Stories of rescue that grip our culture remind us that people were created for the greater Story, for the greater Rescuer. Christ is the ultimate Rescuer. He put Himself in our place on the cross to make us whole, to take away our sin, and to make us right with God. John Stott wrote, “For the essence of sin is man substituting himself for God, while the essence of salvation is God substituting himself for man. Man asserts himself against God and puts himself where only God deserves to be; God sacrifices himself for man and puts himself where only man deserves to be.”