I can’t believe that Kaye and I now have two daughters in high school, which means we have two daughters with phones. Time has sure flown by—just like everyone said it would. It does not feel like nearly seven years ago when I first wrote about us waiting until our daughters turned 14 before we gave them phones. I had read Jean Twenge’s book, iGen, and I was struck by the research showing the negative impacts on young teenagers (less sleep, more anxiety, and much more). We ended up waiting even longer than I said back then—until the start of their freshman year. We were the oddball parents. Both are still not on social media (one is close to being). Thankfully there is more and more research and writing that can be helpful in these conversations for parents and educators—such as The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt, which has helped me feel more strongly about holding off on social media until junior year.

The starting point for us has been conversations about what we desire our relationship with technology to be. We don’t believe technology is evil, and we know it can be used for pure reasons, but we want to use technology wisely. Here are four questions we try to ask ourselves as a family and Kaye and I ask as we make decisions related to technology.

1. Why do I want to use this?

There are pure reasons to use technology. It can help you create, make you more efficient, and connect you with others. I want to use Google Maps to get somewhere. I don’t ever want to pull a map out of my glovebox again. But there are impure reasons too. Many have poked fun at the tech platforms of our day and linked them to the seven deadly sins. There are healthy reasons for using some technology, but asking yourself “Why am I wanting to use this?” is wise.

2. What is the goal and the worldview of the creators?

Last year when the unmanned balloon from China was spotted flying over the US, people were concerned about China spying. I thought, “Of course, shoot the thing down,” but I was amused that people were tweeting and Instagram posting expressing deep frustration that they were being tracked…all the while being tracked as they expressed that frustration. A balloon is not necessary to track us when we have devices in our pockets.

When it comes to social media, we are not the customer. We don’t pay, so we can’t be the customer. The customer is the people who pay for advertising for our eyeballs, which makes us the product. You are the product. Your attention is offered as the product to the advertisers. Thus, the goal of the platform is to keep you on as long as possible. Because the algorithm is often designed to keep you on the app, more articles like the ones you previously reacted to are served up to you. In the documentary, The Social Dilemma, the filmmakers show that what you have read is not what your neighbor has read. You can think the person next to you is foolish because you assume they read the same thing, but they don’t think like you. But they have seen something different, and they think you must be crazy. The goal of keeping us on the app has increased our frustration with others and our world. The goal of keeping us on is making us more frustrated.

As artificial intelligence (AI) is being introduced into our lives, the worldviews of those who program the AI are also being presented to us. Not just the goals, but the worldviews. We are now in new territory. When you type a question into AI, the answer is informed by the worldview of those who fed the information to the machine. As an example, several people have demonstrated that when they type in that they are an adolescent desiring to transition their gender, ChatGPT celebrates their decision and gives specific advice, even suggesting contacting an attorney. And yet when the person types in that they are a parent and asks ChatGPT for help on writing the teenager a letter to encourage the teenager not to transition, AI has refused and told the parent to be more inclusive.

Technology has outpaced our ethical conversations, which is why we should rejoice when Christians enter the tech space professionally. We want Christians at the tables where decisions are being made. We want Christians doing excellent work as they code and design and write business requirements and use cases so they are at the table when ethical conversations occur.

3. What is it doing to me?

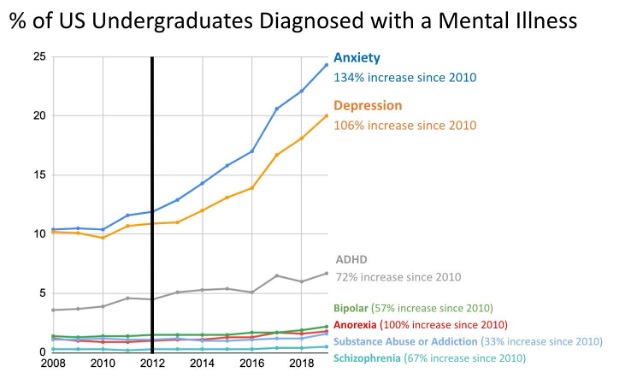

We often ask ourselves, “What can I do with this tech tool?” A better question is, “What is this tool doing to me?” Or, “Is it helping my mind be renewed?” Jonathan Haidt is a social psychologist and professor at NYU. He has shared lots of research on social media’s impact on us—particularly on teenagers. Here is one chart he recently released:

Anxiety and Depression skyrocketed from 2012 to 2018 among undergraduates, at epidemic proportions. Haidt articulates that the epidemic began in 2012 when smart phone use connected with social media skyrocketed among adolescents. If a technology tool or platform is making you angrier or more anxious, change your relationship with that platform.

4. What are healthy practices for me as I use this?

When I was in publishing, I was a power-user on Twitter. We announced the launch of resources, connected with authors and people we served, all good things. But I also noticed the more I used it, the more frustrated I would become. It can be an angry place. I learned to put safeguards around myself. I deleted Twitter from my phone for a season so that I would only be able to check it from my computer. Still today when I am on study break, I delete social media from my phone because social media has pulled me away from deep thinking. If you decide that the tech tool has more upside than downside, set some healthy practices around your use. As a family, we don’t use our phones in the car because that is family talk time, and we don’t have them at the dinner table because we want to be present.